On Aging

- Law Prep with Josh

- On Aging

On Aging

As I write this, I’m 35. I’m starting to notice my parents getting older.

But “age is just a number.” Right? Chronological age should not be a definitive marker of one’s abilities, potential, or societal roles.

Michel Foucault’s ideas on power dynamics within institutions offer insight into parts of society –not just biology — that shape the aging process.

In the past, sovereign power would directly inflict violence on bodies (public executions, torture, etc.), but modern power is more about controlling and normalizing individuals through these institutions. But Foucault’s concept of power is not just about repression or direct control but also about structuring the possible field of action of others. In the context of aging, this means that institutions (healthcare, schools, prisons, the government, and even families) don’t just directly impose restrictions on older individuals; they fundamentally shape the norms, expectations, and ‘acceptable’ behaviors associated with aging.

He coined the concept “of biopower”, the practice of modern states and their regulation of subjects through “an explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugations of bodies and the control of populations” (“The History of Sexuality“).

In that sense we subtly ‘discipline’ the elderly by normalizing certain behaviors and lifestyles while pathologizing others. For example, healthcare systems might promote certain ‘healthy’ lifestyles or retirement plans that psychologically and socially dictate how older individuals should live their post-retirement lives.

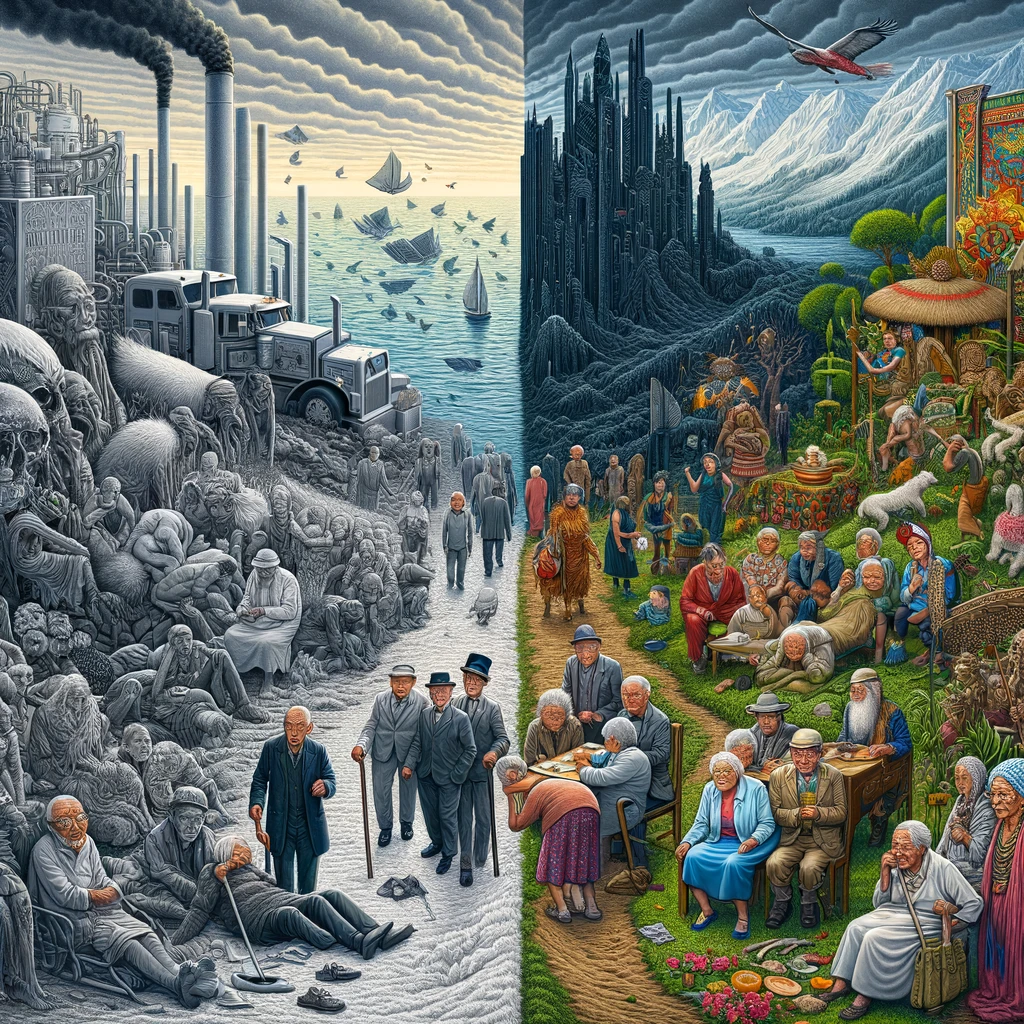

The elderly, in this framework, are subjects undergoing a constant process of ‘correction’ and normalization, where they are expected to conform to a set of restrictive societal standards. We depict the aged as more vulnerable or needy, particularly during disasters. We confine them to restrictive roles like the “perfect grandparent”. We give them supporting roles in their own lives.

A 1986 study examined these stereotypes commonly portrayed in media:

- The Despondent: Elderly characters are shown as isolated, lonely, and sad.

- The Mildly Impaired: Older individuals with minor cognitive or physical difficulties.

- The Vulnerable: The elderly are portrayed as susceptible to abuse or scams.

- The Severely Impaired: Characters with severe dementia or Alzheimer’s.

- The Shrew/Curmudgeon: Older characters are depicted as bitter, complaining, and ill-tempered.

- The Recluse: The Elderly are portrayed as out of touch and secluded.

- The Nosy Neighbor: Older characters are overly interested in others’ affairs.

- The Bag Lady: Depictions of homeless or destitute older women.

Why?

For starters, there’s the obvious: power is wielded to maintain it. Those with power want more power. This desire can be practical (to simplify planning for healthcare and pensions, to manage budgets and resources, especially for increasing healthcare needs) or it can be more naked ambition (by controlling these rules, these entities dominate the decision-making process).

But why denigrate age?

Sure, Big Pharma likely profits from a docile aging population. But corporate greed doesn’t explain all of these institutions (schools, prisons, professions, even families) reflecting societal values that glorify youth and productivity.

I find our cultural fixation with youth and the youthful body unsettling. The media perpetuates a formula where youth equals beauty, vitality, and desirability. The attributes of youth – freedom, rebellion, innovation, and sex appeal – are celebrated as the pinnacle of being alive and vibrant, leading to a perception that aging equals decline and loss. In this narrative, the virtues of wisdom and maturity are undervalued. At least in Western society.

But different cultures understand aging philosophically in varied ways:

Eastern :

Confucian, Taoist and Buddhist views see aging as a journey toward spiritual enlightenment and wisdom, emphasizing interconnectedness and life as a path to enlightenment. In Buddhist philosopher Daisaku Ikeda’s essay “The Third Stage of Life: Aging in Contemporary Society“, he views aging as an opportunity for deepening spiritual understanding and societal contribution, suggesting that with age comes wisdom, which can foster compassion and a sense of interconnectedness.

African (Ubuntu):

Elders are revered as community leaders and advisors, custodians of tradition and history. Philosopher Kwasi Wiredu emphasizes that elders are active participants, serving as moral compasses and custodians of communal harmony. Their role in decision-making is central, reflecting the Ubuntu ethos of consensus and communal living, differing significantly from Western libertarian or individualistic philosophies.

Indigenous:

As explained by Vine Deloria, elders are seen as cultural and spiritual anchors. This view contrasts with Ikeda’s focus on personal wisdom and Wiredu’s emphasis on communal roles. Elders in Indigenous cultures are guardians of cultural and spiritual heritage, playing a vital role in maintaining tribal sovereignty and land rights.

Western Perspective:

Friedrich Nietzsche, though I’m not aware of his thoughts about aging directly, might have critiqued all of the above perspectives for sustaining tradition and communal harmony at the expense of individual self-overcoming and value creation. His work focuses on personal freedom and self-realization, emphasizing autonomy and the quest for meaning — often challenging ethical and traditional frameworks to do so. But you can expect Nietzsche to be spicy.

Simone de Beauvoir, in “The Coming of Age,” highlights the societal construct of aging, often seen as a period of decline. She argues that aging is more than a natural process; societal narratives shape it. Aging, according to her, is not confined to passive activities but is a chance for profound existential reflection. The later years can be a ‘Time of Authenticity,’ free from social norms, embracing life with unapologetic authenticity. Your mortality becomes a liberating force, urging you to define aging on your terms.

Should we try to live indefinitely?

Generally speaking, we don’t want to die. But we also don’t want to suffer. With a limited budget, how do we decide how much of resources to allocate towards prolonging life as opposed to enhancing its quality?

I think Simone de Beauvoir would argue that extending life without considering its meaningfulness is contrary to existentialist ideals: those being that existence precedes essence. We define our essence through our choices within the context of our finite lives. Our awareness of our limits compels the search for meaning in our actions. The mean of life comes not from its duration but from our depth of engagement with our projects and relationships. Without this depth we have a life stretched thin.

African and Eastern philosophies would also emphasize a dignified life that allows for continued community contribution and harmony with nature.

So when we invest heavily in anti-aging research, when we try to radically extend the human lifespan, it reflects a fear of death which is contrary to the acceptance of life’s natural cycle in many cultural teachings. Consider the African context, where there are pressing health crises and inequality in healthcare access: a focus on extending life for the sake of longevity seems misaligned with immediate needs.

Mark Greif suggests: “It will require preferring the values of adulthood: intellect over-enthusiasm, autonomy over adventure, elegance over vitality, sophistication over innocence—and, perhaps, a pursuit of the confirmation or repetition of experience rather than experiences of novelty.”

Josh's LSAT Tutoring

Related Post

Logical Reasoning: Cheat Sheets

Why You Should Do Nothing